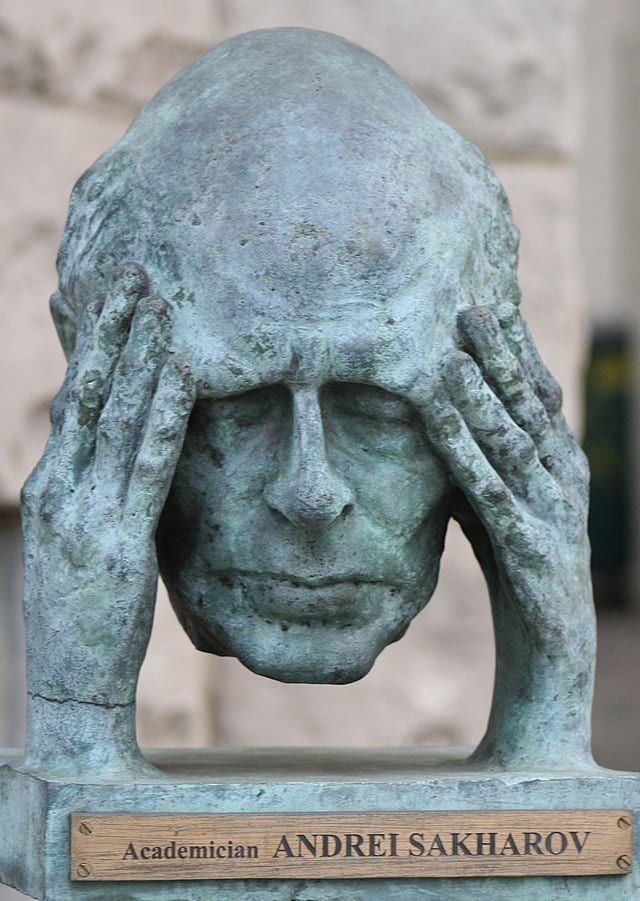

In memory of Andrei Sakharov, who would have turned 100 on 21 May 2021. How would he celebrate his 100th birthday today?

On 14 December 1989, Andrei Sakharov died at the age of 68, Muscovites bid farewell.

December 1989, it is minus 40 degrees, everything was covered with snow and ice, and I was standing in a queue of people with no end in sight. A young political science student from Goethe University (Frankfurt am Main) from West Germany was standing in the longest queue she had ever seen. Shivering, wearing a fur coat and a man’s sheepskin hat. One must say she looked quite strange in comparison to the others, but no one was looking at her. Even burly fur coats could not save people from the Siberian frost. There was a venerable, contemplative silence all around, no one asked the person in front why he was standing there, nor did anyone tell him that they were standing behind him. There was no disorderly bustle back and forth, so typical for the daily Soviet queues to which she had become accustomed five months after her arrival to Moscow.

No, it was something else entirely, something great, in that Siberian cold, in which even saliva froze instantly on the face, it was the Russian soul, languidly breathing warmth. All of them lined up here in that queue, having stood for countless hours, already in the dark of night, to pay their respects to the man who had touched their souls so deeply. Andrei Sakharov.

Who was this man? This is certainly not a question for the older generation, but for the younger generation the question is quite justified. Simply put, he was a kind of Mahatma Gandhi from the East.

Andrei Sakharov was a world-renowned nuclear physicist, the chief developer of the Soviet hydrogen bomb. But the hellish significance of what he created led him, as well as his colleague on the other side of the Iron Curtain at the height of the Cold War, Robert Oppenheimer, to an existential process of social responsibility.

Initially convinced that a balance of atomic weapons of the two world powers could guarantee peace and security, he replaced the atomic balance in this peace formula by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and discovered that in his country the factor he now considered as a crucial one was no more than a springboard by means of which the equation could not be derived in this way.

Yes, of course, such a correction of the formula does not require mathematical genius and does not raise him to the level of Mahatma Gandhi.

The question arises, to what extent am I personally prepared to vouch for this formula?

Imagine a world divided into two irreconcilable competing world powers, one defined by the fact that it possessed the only correct formula for peace and freedom, that it fought for human rights. How much courage it took at the height of that successful formula for Andrei Sakharov, as a leader of scientific achievements, as a leading representative of the Soviet intelligentsia, as a significant figure, to stand up before world public opinion and prove that this basic formula of his country was wrong and, moreover, that here they were fighting not for respect for human rights, but against that respect.

And ultimately it is also the inherent charisma of the man, which Andrei Sakharov undoubtedly possessed.

It was not so much his scientific genius as his human warmth and wisdom that disposed people.

Since the late 1960s Sakharov has taken a very concrete stance and written many philosophical essays on fundamental questions of peace and freedom. He advocated a reassessment of the Stalinist terror, condemned the suppression of the Prague Spring, always advocated non-violent resistance, appealed to the Soviet authorities in open letters for the democratisation of the country, kept informed about the fate of political prisoners and their tortures (including in psychiatry), personally went on hunger strike for their release, supported oppressed minorities, worked on a new constitution, stressed the fundamental importance of a functioning constitutional state and intellectual freedom.

Since the late 1960s Sakharov has taken a very concrete stance and written many philosophical essays on fundamental questions of peace and freedom. He advocated a reassessment of the Stalinist terror, condemned the suppression of the Prague Spring, always advocated non-violent resistance, appealed to the Soviet authorities in open letters for the democratisation of the country, kept informed about the fate of political prisoners and their tortures (including in psychiatry), personally went on hunger strike for their release, supported oppressed minorities, worked on a new constitution, stressed the fundamental importance of a functioning constitutional state and intellectual freedom.

And it goes without saying that from the hero of the state No. 1 he turned into an enemy of the state of the first category of the KGB. From an international role model to forced exile to Gorky under the supervision of a special KGB unit.

It goes without saying that he did not personally receive the Nobel Peace Prize, awarded to him in 1975; instead, the prize was received by his second wife, Elena Bonner, who was forced to follow him into exile to Gorky in 1984.

In December 1986 Mikhail Gorbachev personally telephoned Sakharov (the telephone was installed in Sakharov’s house the night before), cancelled his exile and brought him back to Moscow.

And exactly two years later I stood here, in this endless queue, in this Siberian cold, among Russian souls who wanted only one thing here: to pay their respects to the deceased.

Although I had grown to love this country and its people during the year I spent in the Soviet Union, after standing for three hours in a completely unmoving queue, I left like an iceberg, irrevocably abandoning my place in line, hard-won, but touched by the fact that I had the privilege of being part of such a special historical moment.

The life of Andrei Sakharov mirrors the history of ISHR’s creation.

Andrei Sakharov was the perfect role model for the Russian émigré and virtually Sakharov’s peer Ivan Agrusov, the founder of ISHR, who was declared an enemy of the state by the KGB in the early 1970s, and with him the entire ISHR, which the Stasi persecuted like no other organisation.

It goes without saying that the two were not allowed to meet; the earlier implicit agreement to become Honorary Chairman of ISHR was rejected by Sakharov in his letter to ISHR in October 1982:

“Dear friends, it is with great interest and gratitude that I have received word that ISHR is doing such outstanding work in defending prisoners of conscience and against other human rights violations … from the bottom of my heart I wish you success… as to your proposal of my election as a Honorary Chairman, I must inform you that I cannot accept it… in view of my almost complete isolation… Andrei Sakharov”.

How would Sakharov have celebrated his 100th birthday today, on 21 May 2021? Would he have had a proper ceremony in Moscow, would he have been able to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo?

In Russia, the planning of such a large-scale celebration will be undertaken by Memorial organisation, whose founding chairman he became shortly after his exile and before his death. Memorial is primarily dedicated to the re-evaluation of the Stalinist terror and the rehabilitation of its victims and is by far the largest and best known human rights organisation in Russia.

It was thus one of the first of nearly 200 non-governmental organisations to fall under the 2012 law “On Foreign Agents”.

The law emerged after large-scale street protests in 2012 and was justified by the need to protect against foreign influence damaging the state.

Organisations that receive funds from abroad and are active in socio-political activities have since been required to undergo a special audit of their finances and documentation and to list themselves as “foreign agents” in all their documents. The law “On Foreign Agents” is characterised by largely vague legal terms and definitions, and for the most part a judge has a very wide and arbitrary range of interpretation as to which NGOs he can declare a foreign agent and what sentence (up to high fines and imprisonment as well as closure of the organisation) he can impose.

Just after the law was passed, I myself was in Moscow at the time to attend the annual general conference of the Russian section of ISHR. After many years of working in good conditions, it was a clear cut, old fears appeared, I kept looking around to see if a horde of OMON officers (special forces) were going to rush out of that white bus at us and put us in jail.

But nothing of the sort was noticed, except by the usual officers of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, who, in turn, observed what was going on.

But to link the new law on agents with the beginning of the Stalinist terror, as many Russian colleagues did, seemed to me an over-exaggeration.

But they warned that this law would not be the end, it would only be the cornerstone for further and more radical restrictions on civil society. And they turned out to be right.

The phenomenon of suppression of any confrontation in the bud by the increasingly harsh laws of the Russian State Duma, which are superior in their absurdity, has a stable phrase in the Russian language, namely “mad printer”.

A long-established phenomenon of autocratic and dictatorial systems which, at least until now, have been trying to maintain an appearance of legitimacy.

For those who have little idea what this means, it is enough to recall the plot of the fifth book about Harry Potter, when the Grand Inquisitor Dolores Umbridge hung new school decrees on the high walls of Hogwarts every day in order to prevent pupils from forming Dumbledore’s Army.

The cornerstone of the defamatory law on foreign agents was the adopted in 2015 law “On Undesirable Foreign Organisations”, namely those that provide financial support to “Russian foreign agents”.

The following year, the existing anti-extremist legislation was massively expanded (“Yarovaya Legislative Package”) to cover all areas of independent media, including personal use of the Internet. Telecommunication providers have been held liable for the content of their users, prosecution of bloggers and social media users has been given almost unlimited scope and the maximum possible range of punishment (from the age of 14 to 8 years of imprisonment). However, since the law “On Extremism” lacks a precise legal definition of its “namesake” (extremism), it is subject to a very wide and arbitrary interpretation, both by the police apparatus and the judiciary. A flexible law for “all occasions”.

At the end of 2019, the mad printer started up again with redoubled force when President Putin initiated a major constitutional reform. In the shortest time, a package of more than 170 constitutional amendments was drawn up, which together tighten the autocratic state structure of the Russian Federation.

Thus 450 deputies of the State Duma, three quarters of whom are from the ruling United Russia party, have thus officially made themselves more dependent on the upper system than on their people.

Spurred on by the magical functional power of its mad printer as part of a major constitutional reform, the incalculable extensions of the law “On Foreign Agents” appeared that year in the criminal legislation, not least in connection with the State Duma elections (once every 5 years) in September this year.

From now on organisations receiving foreign funding must now independently register with state authorities as foreign agents.

Foreign funding now includes not only financial resources but also material support, it can easily be a computer, printer, copy machine or toilet paper.

Internal promotion of an organisation listed as a foreign agent is also prohibited. They are not allowed to receive any support from the business community, they are not allowed to conduct their own crowdfunding funding and they do not receive any state funds for the NGO, which amounted to over 111 million euros this year.

At the beginning of 2021, the rabid printer was able to spit out a very special law whereby the law “On Foreign Agents” now applies not only to organisations but also to “individuals” who are “politically” connected to such an organisation. It is clear that the term “political” has no precise legal definition, so simply attending an event can arise serious criminal consequences. In addition, the individual must himself or herself apply for the “title” of foreign agent and make it publicly recognisable.

The education legislative initiative, already discussed during my last visit to Russia in November 2018, is now in a state of drought: it affects all “intelligence and educational institutions” that communicate with foreign scientists. Inviting a foreign scientist now requires the approval of the competent ministry, and the content of the communication must also be verified by the state. It goes without saying that the term “intelligence”, as reintroduced here, is legally very broad.

The mad printer also proves to be a magic tool in the run-up to the upcoming State Duma elections: foreign agents are banned from any election-related activities.

For example, the only independent election institute (also listed as a foreign agent), founded by the world-renowned social scientist Yuri Levada, is no longer allowed to publish voter surveys.

Particularly for the duration of the election campaign, it is not only the association, organisation and individual of “foreign agents” that is screened out, but also the “affiliated” organisation or person. It is understood that the term “affiliated” has no precise legal definition.

So if somewhere in a tiny corner of the largest country in the world the election result does not match the state’s wishes, it is easy to prove that someone who knows someone was involved in the electoral process…

Against this background, and without taking the pandemic situation into account, the previous, purely hypothetical question can nevertheless be answered in great detail:

How would Andrei Sakharov celebrate his 100th birthday today, on 21 May 2021? Would there be a proper celebration in Moscow?

Well, let’s start with the planning procedure, his organisation Memorial at least no longer has to go through complicated official procedures to obtain the necessary registration as a foreign agent, the state has taken care of this in advance. All invitations should be clearly labeled as “foreign agent”. They will be prohibited from receiving any financial or other in-kind donations, whether domestic or from abroad. There will be also no state support.

They will have to submit an official application to the relevant ministry for every foreign scientist they invite and keep an officially verifiable record of every interview with them if they are allowed, as well as verify every birthday present.

Celebrating as a private person also falls under these conditions, as Andrei Sakharov will now be registered as a foreign agent as a private person. Anyone attending the party could also be classified as a foreign agent by attending it. Or at least as “affiliated”, and therefore would not be entitled to participate in any way in the electoral process, let alone stand for candidacy.

Would he have been able to receive personally the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo nowadays?

Here the question remains largely hypothetical. He would surely have taken the opportunity to oppose the law on “On Foreign Agents”, to take a stand on Crimea, Ossetia, Transnistria, Chechnya or Karabakh, to advocate a reassessment of the Stalinist terror, to condemn the suppression of the Belarusian Summer, to call on the Russian Federation to democratise the country, to present his concept of a new constitution which he developed 50 years ago and which seems more democratic than the hastily implemented constitutional reform nowadays in Russia. He would stress the fundamental importance of a functioning constitutional state and intellectual freedom.

He would certainly have reported Alexei Navalny’s health condition in prison, and if it was as threatening as is now being reported, he – even assuming the two are not on the same page – would have gone on hunger strike for him.

If his own health could not withstand all this at the venerable age of 100, the same rules would apply to his funeral service as those for the hypothetical anniversary celebration listed above.

Moreover, during the adoption of new laws “On Tougher Penalties for Disobeying the Police” queues at these kinds of events were completely banned. So the question of whether this mourning queue, in which I stood then, in a harsh Russian winter, shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union, today, after 32 years of “modernisation”, could say so reverently goodbye, still remains unanswered.

Farewell to one of us, to someone who could rank with the world’s great thinkers, who was respected and loved, who opened up his painful experiences to the world without showing them off, who expressed his desire for international understanding, peace and freedom not only for the then Soviet Union, but for the world, and who personally suffered in the name of realising all of the above.

It was felt then, in December 1989, in that special, silent row of people, that this was the real farewell, remembered as one of the most moving historical moments in life.

Dr. phil. Carmen Krusch-Grün

International Society for Human Rights

Leave A Comment