A translation from the ISHR from an article published in the Russian oppositional newspaper, the Nowaja Gaseta (New Newspaper) from September 3, 2014: http://www.novayagazeta.ru/society/65075.html. Published with permission from Elena Ratcheva and the Nowaja Gaseta.

The coffin, in which Anton Tumanov arrived in at home, was locked. “There was a small window, through which at least the face could be recognized”. The boys told me, that only shreds of flesh remained of some of guys in their unit, and DNA tests are now underway. The parents haven’t received their children back yet.”

Anton’s mother, Yelena Petrovna Tumanova, sits on the living room sofa where Anton used to sleep. She straightens the black mourning veil over her short gray hair and searches for her son’s death certificate in her pocket – for some reason she carries it with her.

The personal belongings and military service identity card of Sergeant Anton Tumanov have not yet been returned to his mother. On August 20, she received only the coffin and a copy of the death certificate from Rostov’s morgue. The date of death recorded reads: The 13th of August 2014; the place: “Temporary station of the military unit 27777”, period of time: “During the execution of his military service”, the cause of death: “whole body failure”; fragmentation injuries of the lower limbs with destruction of the large blood vessels; massive blood loss.”

“His legs were torn off, of course. The boys told me, but I also could tell that it was not his whole body in the coffin.”

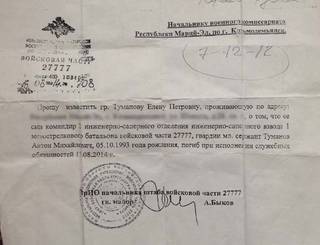

The message from the commandos of military unite 27777, that Anton died ‘carrying out his military service’.

Anton joined the army in 2012 in Kosmodemjansk (21,000 inhabitants, 100 km from Joschkar-Ola, the capital of the Voli, part of the republic of Mari El). He completed his basic military training in Pensa in Central Russia, and carried out his military service in South Ossetia in the South Caucasus.

“When he came home after his military service, he wanted to find work, but he did not succeed,” says Elena Petrovna calmly. “The did not accept him as a staff member in the detention center because of anemia. He was made for the army, but not for that job. Anton then went to Nizhny Novgorod, where he spent three months working in a car factory. He was unable to find a place to stay and to rent was too expensive. He came back. He traveled to Moscow a couple of times, and worked at a construction site with some young men there. He was never paid his salary, and I had to pay for his return journey.

The last photo of Anton Tumanov (far right) in the ‘temporary station location’ near Sneschnoje, in the region of Donezk, Ukraine. The photo was taken by a comrade of Anton’s and was put online in VKontakte. The second from the right is Robert Arutjunjan, who is also presumed dead. The fate of the others is uknown.

And where can someone expect to find work here with us in Kosmodemjansk? Only two factories remain here, one makes plastic parts, and I’m not sure what the other one produces at the moment. In May he said, “Mother, I will join the army.” Me: “Wait awhile, you see what’s happening…God forbid, that they send you to the Ukraine. We already had Chechnya, Afghanistan…” Mama, our troops will not be sent there. I have already decided I am going. I need money. I’m not going to war, I’m going to work. There is simply no other work to be had.”

On June 21, Anton went to the 18th Brigade, Unit No. 27777, to the Chechen village of Kalinovskaya. He had chosen the place of work himself. He always said that he really fell in love with the mountains of South Ossetia during his military service: “I would like to see the mountains when I fall asleep, and see the mountains when I wake up.” He hurried to arrive there by the end of the month to get his pay in July, but only in the unit did he find out that there is a three-month probationary period before the beginning of the contract, in which he receives no pay.

“He called and said,” There will not be any money for two months”. “I said,” Tell me honestly, should I send you money? “, Yelena Petrovna says,” Well, whatever you can spare.” I sent him 3,000 rubles (about 50€), as much as I could muster; I am a nurse who earns 5,500 rubles a month (about € 110).

Anton told me that they were all sitting there without money, that their pay had been delayed. When the boys arrived from his unit after the funeral, they brought his documents, which showed that they had not received any allowance apart from the train tickets, only those tickets, and off with them. They only got something to eat here.”

Anton never was never paid for his one and a half months of service. He told his family that they had promised him 40-50,000 rubles (about 1,000 euros). His comrades declared that Anton had apparently been swindled; they would not get more than 30,000 (about 600 euros).

“We’re going to war”

The likely late Robert Arutjunjan und Anton. In the region of Rostov.

Anton called home almost every day. At the beginning of June, he suddenly declared: “They asked who wants to volunteer in the Ukraine from our unit”.

I told him, “I hope very much, that you don’t?” He replied: “Am I an idiot? No one here wants to go.” One of the guys went together with him, who had also landed in Chechnya, in Shali. He told me later that they were told by their unit that “If you stay a few days in the Ukraine, you will get 400,000 rubles” (about 7,000€). Of course, no one agreed, because even if they survived, they would have been cheated with the money anyways.

Then Anton wrote to his mother that he was sent to an area near Rostov-Don. On the Russian-Ukrainian border,

the soldiers of Unit No. 27777, according to his words, arrived on July 11. Yelena Petrovna was not worried:”It is warm in Rostov, Ukraine is far away, and everything is going well for Anton. What does ‘going well’ mean?” I asked him, “What have you eaten?” – “Instant noodles (Doschirak)”. “And what about the field kitchen?” – “There isn’t one. Only dry food”.

Elena Petrovna is still indignant at the fact that the boys were so badly fed, and that they were exposed to wind and weather. She seems to cling to the idea that her son has starved. She cannot imagine him dead.

Anton’s fiancée, 17-year-old Nastia (Anastasia) Chernova, discusses this month in the Rostov region very differently. Like Elena Petrovna, she wears a mourning veil in her hair. She sits on the sofa opposite Anton ‘s picture: small, very petite, with long blond hair, and all in black (“I cannot wear anything colorful, purely physically I cannot do it”). During the whole conversation, she does not raise her head once.

Nastia spoke with Anton every day, and he told her much more about the military service than his mother. On July 23 or 25, he said for the first time, “We’re going to war.” The frightened Nastia only asked: “I thought there aren’t any Russians in the Ukraine anymore?” He replied, “We act as insurgents”. After that, there was no contact for three to four days.

The second time, as Anton told Nastia, they were sent to the Ukraine on August 3 for two days. He did not mention the cities, the duration, or the objectives of the order to march; Nastia suspects he did not know for himself. She said “Most likely, they were sent simply to control the situation, to go, look, and observe”. “They were given Ukrainian money, and Anton had told me he went into a store and laughed “There are no souvenirs, but at least I can get Ukrainian money home. As if there was no war. Just as if it were everyday life.”

“Sent to the support the insurgents, do not worry; everything will be chiki (okay)”

On August 10, Anton called home: “Mama, we are being sent to Donetsk.”

“I answered, “Where? There is war there! You must not be sent there!” He replied: “Mom, that’s just what you think. They are sending us to help the insurgents, do not worry, everything will be chiki!”

He also told Nastia that he would be in the Ukraine for two to three months, possibly until November, without access to a telephone.

“Just before he left, he said,” I do not want to go, we thought about jumping from the van with the guys, but it’s just too far back to the unit, one and a half thousand kilometers,” Nastia recalls. “Maybe he had foreseen it…over the last few days, he often said: “I haven’t married and I have no children, I have nothing…” These were his plans, his desires….”

On August 11, Anton was handed two hand grenades and 150 rounds of ammunition for a machine gun. At 3:00 pm, he sent his mother a message that read “Work cellphone delivered, departed to Ukraine” over the social network “VKontakte”. That was all…

“I cannot understand how they could send them,” says his mother. “There were many of them, 1200 people…I did not even know who to call, I didn’t know the majors names, let alone their telephone numbers… If I had known someone, I would have said, “How dare you send him there! I would have…if I had known.”

We learned about what happened after that from the reports of two of Anton’s comrades out of Unit 277777, who brought his documents with them after his funeral. One of them left Yelena Petrovna a notarized “explanation” with the details of Anton’s death. Later, he was prepared to meet with Sergei Krivenko, a member of the Human Rights Council and memorial board member, who recorded his report in order to question the military investigative authority.

According to his comrades, the order to cross the border with the Ukraine took place on August 11. Those who refused were insulted, berated, and threatened with prosecution. All documents and mobile phones had to be surrendered, the regular uniform replaced with camouflage uniforms, and identification marks were painted on the vehicles and license plates. Narrow white bands were tied to the legs or hands. Later, Ms. Tumanov found a photo of her son wearing such bands in the VKontakte network, marked with the comment of his comrade: “Identification marks for ‘ours’ or ‘alien’, today on the ankle, tomorrow on the right arm and so on. Those who move without a band: destroy.

Elena P. Tumanov auf dem Grab ihres Sohnes

On the night of August 12, a column of 1,200 men marched into the Ukraine and stopped on the site of a factory in the city of Sneshnoje in the Donetsk region, 15 kilometers from the border. The transporters with weapons and ammunition were placed close together. On August 13, the column was attacked by rocket launchers.

“The boys said that of the 1,200 men, 120 were killed and 450 were wounded,” says Ms. Tumanova. “They themselves were somewhere towards the back, but my Anton was in the front, with no trenches, no shelter…panic broke out, who was in a car, whoever else … Everyone tried to save themselves as they could…”

In short, the description of the operation of the victorious Russian army in a foreign country was as follows: According to the description of Anton’s comrades, a military column marched into the Ukraine with two grenades per man and without military equipment, and returned within one day with 120 dead bodies.

“Did you give the order?”

The notification of Anton’s death came from Mr. Budaev, a staff member in the recruitment office of Kosmodemyansk. “At the time, he had pulled Anton into regular military service, and he was now the one who issued the contract. He brought the message, and cried. I just asked, “Where did it happen?” – “At Lugansk.” “But they were sent to Donetsk!” “They didn’t make it there.” He gave me the phone number of the unit, I called and asked, “Maybe it was just a mistake and not my son after all?” “No, everything is certain; the men have just identified him. My condolences and sympathies…”

Since then, no one from the military command has spoken with Yelena Petrovna. And she no longer calls, because she doesn’t know who to call.

“Why did this happen? Where? I should just say it and not lie. Most of all, I naturally want to know why, and who, gave this command? The command could only have come from Moscow. If Putin stood before me, I would ask him exactly that: “Did you give the order? Answer me honestly.” I thought until the very last day that there were no Russians there. However, the guys say that there won’t be an end there for a long time. Why do people have to go there? Let them go their own way as they please. ”

She cries.

“It’s been happening since the beginning of the year already, or maybe even earlier, no? As they gained Crimea, I watched TV and thought, “Why on earth do we need that? As if we are not far away and forgotten enough, then we get someone else involved.

Anton didn’t seem to think about it. He didn’t go to fight, but rather to work. ”

At the request of Yelena Petrovna, I am helping her write an appeal to human rights activists and will take it to Moscow.

“I started to panic. I want people to know that our men are fighting. Although in Moscow, maybe everyone know about it except for us?” She asks very seriously. I sink my head and say nothing. I call the ‘Soldier’s Mothers’, and they immediately say: “Yes, the 18th Brigade, 120 dead, we know.” That means I’m not the first person to call her. They ask me, “Aren’t you afraid that you’ll be… you already know what …?” “I’m not afraid,” I say.

Ms. Tumanova has reported the death of her son on the homepage of the network “Odnoklassniki” (classmates). In response, she received dozens of malicious remarks about the fact that she was lying, denigrating the Fatherland, and making PR. “One wrote: ‘Are not you afraid that the devil will get you at night…?’ I thought she was kind of strange, though she looks quite normal in the photo.”

“Do you want anyone to be punished for Anton’s death?” I asked them.

“To be honest, whether or not someone loses their post doesn’t matter at all to me. I just want to know why he was sent there, who did it? Only for myself. However, it is very difficult for someone to be daring enough to talk.

The Cemetery

In the lower part of Kosmodemjansk, closer to the Volga, there are old blackened blockhouses. Colorful borders, palisades, boats in the yard. It looks like a big village. Not in a way that would be very depressing – like everywhere else. From the house to the cemetery is a fifteen-minute walk. On the way, we find mushrooms right on the street and buy wilting dahlias and asters on the empty market.

“Why are they fighting?” Yelena Petrovna asks me, not purely rhetorically, and stumbles on the cracked pavement. “Because of the territory, or what? Who needs it, I can’t understand this policy… Before, I sometimes thought: ‘Who fights there?’ When it is constantly reported, how many insurgents are killed – how many of them are left? Anton was already near Rostov, and I had always thought exactly that. Which is how some of the people here see it. The Second World War didn’t reach us, and this war won’t reach us either. That the men get pulled into it, just doesn’t make any sense.

Between the old tombs, which have long ceased to be tended, with photographs of serious old women with headscarves, Anton’s grave immediately stands out. Plastic wreaths from relatives and the military commissariat (Russian military agency), a bottle of fresh field flowers, the photograph – in military uniform. Yelena Petrovna distributes sweets on the grave: “Delicious, with raisins, bought today,” and removes the flower bouquets, which are scarcely faded after the funeral. She crosses herself and cries.

“A lot of people came to the funeral. The military officials brought a military orchestra from Joschkar-Ola; the orchestra that always buries soldiers. They told me that Anton was not the first of our Autonomous Republic of Mari El who has fallen there.”

The soldiers who came from military unit 27777 told Elena Tumanowa that they brought the mission documents of three fallen soldiers for their families, in Kosmodemyansk, Kazan and Marinskij Posad.

A comrade of Anton’s placed a photo in “Vkontakte”, showing Anton with another smiling comrade. Underneath it: “Robert Martunovich Arutjunjan, Anton Tumanov. Heroes that died while performing their military service.” In the comments: questions about their unit and the place of death. Answer: “Technical news group of the marching battalions, Sneshnoje, in one of the Eastern European countries.” “And what did they do in Eastern Europe?” asked the next question. Answer: “We have carried out an order in the function of insurgents.” By the way, I was replaced by parachute troops from the Pskov troops, who supposedly have nothing to do with South-East Europe.” [Note by the IGFM: Reportedly, another 80 soldiers from this exact airborne group have fallen in the Eastern Ukraine and were secretly buried.]

Letting Go

“We have to let him go. 40 days are given for that. It is said that if we cry, it goes badly for him up there. We cannot cry,” says Yelena Petrovna. We sit in the kitchen, Mrs. Tumanowa tries to prepare lunch for us and Nastia; she cuts generously thick sausage slices. Nastia stirs her tea with an absent gaze.

When I called him for the last time, he didn’t have a single cent for a phonecall, remembers Yelena Petrovna. I said, “Well, I’ll hang up now.” He replied, “No mom, don’t hang up. When I get back, I’ll call you and then you can hang up.” Can you imagine?” She cries.

A journalist comes from the “Red City” from Joschka-Ola to visit Mrs. Tumanova at the same time as myself. He persistently asks whether Anton has done sports, or if he was good in school. Clearly, he was writing a hero portrait. “No, not really,” Yelena Petrovna shrugs slightly. “He wasn’t especially good at school. When he finished, school wasn’t going anywhere so he went to technical school, but he didn’t finish it.

He said you don’t need a technical degree to work in a factory. There aren’t any universities in our city. What he wanted was to work, have a car, own an apartment and marry. Only it didn’t happen because of the work situation…but you know, I did always want to see him in a uniform, and he himself enjoyed serving.”

The whole city is aware of Anton’s death. Smiling, Yelena Petrovna recalls how many girls came to her and said how much they liked Anton. “I was afraid to see him dead, and as long as I had not seen him, I did not believe it.” Nastia continues to stare at the ground. She searches for words very carefully and earnestly. The words do not seem to obey her, but she continues as if it absolutely needed to be, saying “When we were together, I was not afraid of anything. There was nothing to be afraid of. He promised that when he came during New Years on vacation, we would marry. I said it was too early for me to marry, but if he had come with a ring, I would absolutely not have said no. I asked, “Why so early …?” and he answered: “Because suddenly there’s war, and we have no children – at least we can marry.”

Redaktion der Nowaja Gaseta: Wir möchten bemerken dass in gegebenem Fall sich die Militärbehörde anständig und menschlich verhalten hat.