They are courageous: young people who protest in Russia against the war in Ukraine face severe penalties. They serve as a deterrent for imitators.

‘Do you need a president like that?’ These words were written on leaflets by 15-year-old Arseniy Turbin from Livny and distributed through neighbours’ letterboxes.

On 20 June, he was sentenced to five years in prison by a military court in Moscow. The reason given was that he was part of a ‘terrorist organisation’. His lawyer has lodged an appeal, but the prospects of a reduced sentence are slim.

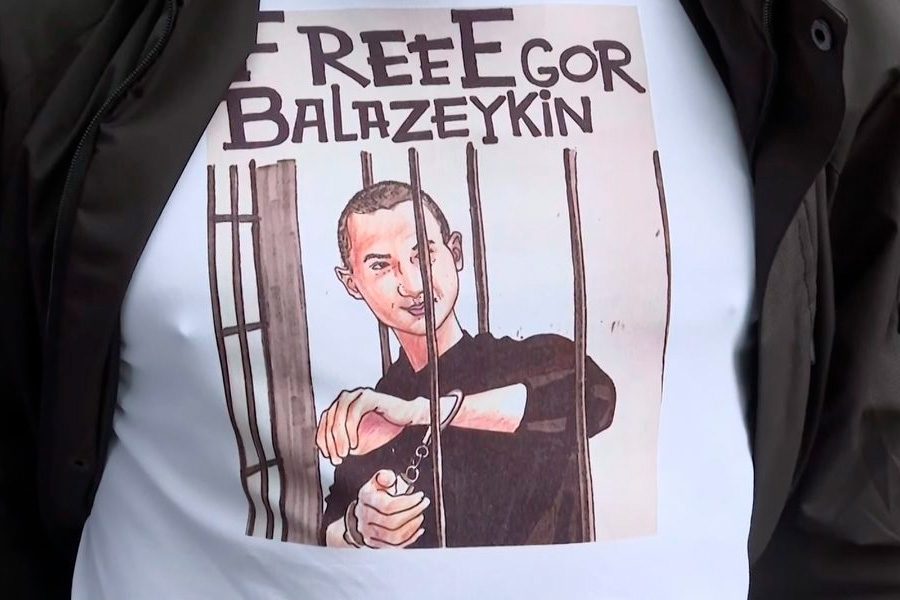

Schoolboy Egor Balasejkin has also been behind bars for a year and a half. At the age of 16, he threw a homemade Molotov cocktail, which failed to ignite, at a conscription centre at night. The building was empty. As a 17-year-old, he was sentenced to six years in prison in St. Petersburg, guarded by 15 masked police officers – for attempted terrorist attacks.

In his last words in the courtroom, in which Russian defendants are given the opportunity to speak once more, he asked all those who loved him to ask themselves the question: ‘Do you still need this war’?

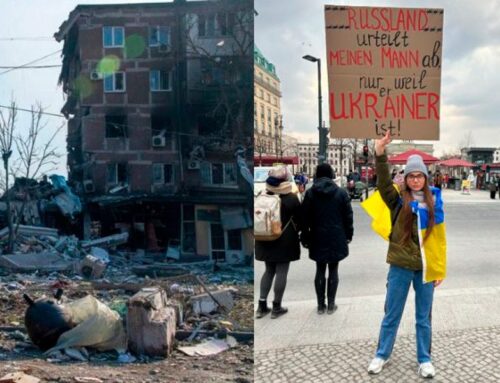

His parents, long apolitical, now realise what a repressive state they live in. Minors who express their protest against the war are turned into terrorists, as this allows the Russian judiciary to impose higher penalties.

Human rights activist Oleg Orlov was sentenced to two and a half years in prison by a Moscow court for his public criticism of the war in Ukraine.27.02.2024 |

Valerio Krüger from the International Society for Human Rights says: ‘Putin is showing his clear face here with complete harshness.’

The aim here is to intimidate young opponents of the war. Anyone who speaks out against the war will be condemned with the full rigour of the terrorist laws.

Valerio Krüger, International Society for Human Rights

According to Krüger, Putin’s main aim is to deter.

Mother: My son no longer wants to keep quiet

His mother describes how Egor seemed almost relieved when he was arrested. He simply no longer wanted to remain silent about the war.

Letters to political prisoners

At the party headquarters in Moscow of Yabloko, Russia’s only significant opposition party, they write letters to political prisoners. The Russians who come here are brave. Because they too can quickly become the target of the authorities. There are a conspicuous number of young people.

Anastasia is one of them: ‘I think it’s important to write more to the younger political prisoners, for example those my age, I’m 18 years old. And I honestly still can’t imagine that there are political prisoners of that age.’

These long prison sentences for children who are just coming of age – if they serve the full sentence and then get out, they are broken people.

Nabi, 18 years old

Those who oppose Putin’s authoritarian regime take high risks. This award-winning documentary follows three young opposition politicians in the months leading up to the parliamentary elections in Russia in September 2021.09.10.2022

Rising number of young political prisoners

An estimated 130 children and young people are serving time as political prisoners in Putin’s prisons. The numbers are rising. Daria Kozyreva is probably the best-known young anti-war activist behind bars.

The medical student from St. Petersburg had pinned a poem to a monument to a Ukrainian writer. In February, she was imprisoned for ‘discrediting the army’. The judgement is still pending. ZDF was able to speak to her 18-year-old fiancé: ‘No matter how much pressure they exert,’ he says:

You cannot force her to remain silent, to repent or to admit guilt. She will continue to stand by it.

Fiancé of imprisoned medical student

When Egor Balasejkin is taken into custody from the courthouse last November after the judgement, a dozen supporters are waiting to see him. They shout loudly into the evening sky: ‘Egor, Egor, Egor’. They want to be heard and not give up their fight.

Manuela Conrad reports on Russia, the Caucasus and Central Asia.

Quelle: zdf.de

Leave A Comment